The importance of “Tax Residency”

Whether you are a resident or non-resident of Australia for tax purposes has significant consequences for you.

Primarily, if you are a resident of Australia for tax purposes you will be liable for tax in Australia on income you derive from all sources – including of course from overseas (eg, an overseas bank account, rental property, an interest in a foreign business, etc).

On the other hand, if you are a non-resident of Australia for tax purposes, you will only be liable for tax on income that is sourced in Australia (including capital gains on certain property such as real estate in Australia).

And while there may be difficulty in determining the source of income in some cases, if you are a resident for tax purposes, the principle of liability for tax in Australia on income from all sources remains clear.

Resident of Australia for tax purposes

So, what does it mean to be a resident of Australia for tax purposes?

Well, broadly, it means you “reside” in Australia (as commonly understood), unless the Commissioner is satisfied that your permanent place of abode is outside Australia.

However, a recent decision of the Federal Court has shed some light on this matter – especially the often misunderstood presumption that “connections with Australia” is all that counts.

“Connections with Australia”

The Federal Court case involved a mechanical engineer who was posted to Dubai for a period of six years, followed by a posting to Thailand, but who had continuous family ties to Australia (in that he financially supported his wife and daughters who were living in Perth).

Originally, the taxpayer was found to be a resident of Australia for tax purposes essentially because of his continuous ties to Australia and the fact that he did not establish personal ties overseas while he was living there (other than via his work commitments).

However, the Court found that “connections with Australia” was not the key test but rather the key matter was where one intended to treat as home for the time being, but not necessarily forever, ie, not necessarily “permanently”.

Likewise, it said that the matter of residency is worked out on income year by income year basis (ie, one particular year of income at a time) and it doesn’t mean a person has to have the intention of living in a particular location forever.

Among other things, the case may have implications for people who work overseas on a contract basis for periods of time, but still maintain family ties to Australia.

It may also mean that closer scrutiny will have to be paid to determine a person’s residency on a year by-year basis and not just “locking” them into a residency or non-residency status from the beginning of any relevant change in their circumstances.

And of course, there is also the key issue of when in fact your residency status may change!

We are here to help

Suffice to say, if you find yourself in any such circumstances (eg, you undertake a foreign posting for a period or you decide to move overseas for some time but still maintain connections here), you will need to speak to us about your residency status – and the tax implications thereof.

Changes to preservation age

Since 1 July 2024, the age at which individuals can access their superannuation increased to age 60. So what does this mean for those planning on accessing their superannuation upon reaching this age?

What is preservation age?

Access to superannuation benefits is generally restricted to members who have reached “preservation age”, which is the minimum age at which you can access your superannuation benefits.

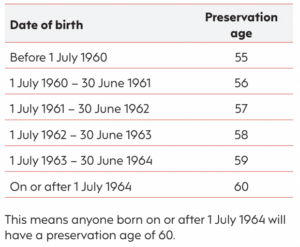

Prior to 1 July 2024, a person’s preservation age could range from 55 to 60 as it depends on their date of birth. Preservation age has been slowly increasing over the years and has finally reached its legislated maximum age limit of age 60, as shown in the table below:

What does this change mean for me?

Once you have reached preservation age, you may receive your superannuation benefits as:

■ A lump sum or as an income stream once you have retired (or a combination of both), or

■ A transition to retirement income stream while you continue to work.

Furthermore, once you turn age 60 your superannuation benefits (ie, any lump sum withdrawals and/or pension payments) will generally be tax-free.

This change simplifies the tax rules as previously those between preservation age and age 60 were subject to tax on lump sum withdrawals and pension payments. Now, the tax treatment of superannuation benefits depends on whether you are above or below age 60 – there is no need to consider preservation age which is based on a person’s date of birth.

Need more information?

If you’re wondering what your superannuation withdrawal options are or how tax may apply to your superannuation benefits, transition to retirement or superannuation income streams, contact us today for a chat.

It’s important to note that preservation age is not the same as your Age Pension age. To get the Age Pension, you must be age 67 or over, depending on when you were born (and other rules you need to meet). So even if you reach preservation age, it could be some time before you are eligible to receive the Age Pension from Services Australia (ie, Centrelink).

CGT & foreign residents: Complex rules apply!

A person who is not a resident of Australia for tax purposes is nevertheless liable for capital gains tax (CGT) on certain assets located in Australia. And these assets are assets which have a “fundamental” connection with Australia – and are broadly as follows:

■ real property (ie, land) located in Australia – including leases over such land;

■ certain interests in Australian “land rich” companies or unit trusts;

■ business assets used in carrying on a business in Australia through a “permanent establishment”; and

■ options or rights over such property.

This means that such assets will be subject to CGT in Australia regardless of the owner’s tax residency status.

Importantly, in relation to real property, this also includes a home that the foreign resident may have owned in Australia. And this home will not be entitled to the CGT exemption for a home if the owner is a foreign resident when they sell or otherwise dispose of it.

Furthermore, a purchaser of property from a foreign resident will be subject to a “withholding tax” requirement, whereby they have to remit a certain percentage of the purchase price to the ATO as an “advance payment” in respect of the foreign resident’s CGT liability. However, this requirement is subject to certain thresholds and variations.

Importantly, a foreign resident will generally not be entitled to the 50% CGT discount on any capital gain that is liable to CGT in Australia – subject to an adjustment for any periods when they owned the asset when they were a resident of Australia.

In relation to a foreign resident’s liability for CGT on certain interests in Australian “land rich” companies or unit trusts, this rule broadly requires the foreign resident to:

■ own at least 10% of the interest in the company or trust at the time of selling the interest (or at any time in the prior two years); and

■ at the time of sale, more than 50% of the assets of the company or trust (by market value) are attributable to land in Australia.

This means that interest owned by foreign residents in private companies and unit trusts can potentially be caught by these rules.

Moreover, the application of these rules can be very difficult, particularly as a foreign resident can be caught by them at certain times and not others.

It is also worth noting that if someone ceases to be an Australia resident and becomes a foreign resident for tax purposes, then they will generally be deemed to have sold such interests at that time and be liable for CGT on them. However, this is subject to the right to opt out of this deemed sale rule – but this “opt-out” has other important CGT consequences.

On the other hand, the rule that applies to make a deceased person liable for CGT in their final tax return for assets that are bequeathed to a foreign resident beneficiary does not apply to certain assets – and these assets are any of the above assets with a “fundamental” connection with Australia.

And this may be further complicated by the fact that, for example, at the time of making the will, the beneficiary may not have been a foreign resident.

The application of Australia’s CGT rules to foreign residents can be very complex – especially given the “variable” nature of some of the rules. Therefore, it is vital to speak to us if you have a “foreign residency” issue.

Selling a small business operated through a company Sell the shares or sell the assets?

If you run a small business through a company and you decide to sell it, you have the choice of either selling the business assets themselves (together with any goodwill) or selling your shares in the company.

Access to the CGT small business concessions

Usually, such decisions are made on the basis of relevant commercial considerations (eg, due diligence and future liability issues).

However, if you are seeking to access the CGT small business concessions on any sale, then you should also consider whether it is better to sell the business assets per se or the shares in the company.

While in principle there should be no difference in terms of the CGT outcome in selling either, it may well be easier to access the concessions by adopting one approach over the other.

For example, if you sell the business assets at the company level you will need to find one or more controllers of the company (ie, broadly someone with a 20% or more interest in it at the relevant time) in order to be able to access the concessions.

And, depending on the circumstances, this can be both easier and harder than it looks.

Furthermore, in the case of the “retirement exemption”, it is necessary to actually pay any exempted capital gain to this controller in order to be able to use the concession (or to put it into their superannuation if they are aged under 55 at the relevant time).

On the other hand, if you can use the “15 year exemption”, it is enough that such a person exists – without the need to pay the exempted gain to them.

“Assets used in carrying on a business”

Most importantly however, if you choose to sell the shares in the company, the company itself must have certain attributes – the most important of which is that 80% or more of its assets (by market value) must be assets used in carrying on a business.

This, in turn, raises the thorny issue of how money in the bank is to be treated – and there is often a fine line between whether it is considered to be used in carrying on a business or not.

More hurdles to jump for eligibility

Furthermore, if the company has “controlling interests” in any other entity, then the assets of any such entity also must be also taken into account in determining if this test is met.

And, of course, as with the application of the CGT small business concessions in any circumstances, the “taxpayer’’ must satisfy either the $2m turnover test or the $6m maximum net asset value (MNAV) test.

And where shares or units are sold, the “taxpayer’’ is the individual who owns the shares and where the business assets are sold the “taxpayer” is the company or trust itself.

In either case, the tests can be difficult to apply because the “taxpayer’’ includes affiliates and connected entities (ie, related parties).

By way of example, if you sell the business assets of a company and you use the $6m MNAV test, then any person who has a 40% or more shareholding in the company will be a connected entity and their assets (other than personal ones such as superannuation and their home) will also have to be taken into account. Importantly, this can include investment properties and shares.

And then there is the difficult task of determining what liabilities relate to those assets for the purposes of this test – especially where the business assets are sold.

Suffice to say, the issues surrounding the question of whether you should sell the business assets of a company or the shares in them when seeking to apply the CGT small business concessions are complex.

Furthermore, the same issues arise in respect of deciding whether to sell the units in a unit trust that operates a small business or the assets of the business itself.

We are here to help

In any of these scenarios we are here to help – as this is a matter which clearly requires the expertise of a tax professional.

Spouse contributions splitting

Splitting superannuation contributions to your spouse can be a great way to boost your combined superannuation balances which can benefit you both in retirement.

What is contribution splitting?

Spouse contribution splitting allows a couple to optimise their superannuation balances by splitting up to 85% of concessional contributions (CCs) they made or received in one financial year (ie, 2023/24) into their spouse’s account the next financial year (ie, 2024/25).

Remember, CCs are before-tax contributions and are generally taxed at 15% within your fund. This is the most common type of contribution individuals receive as it includes superannuation guarantee (SG) payments your employer makes into your fund on your behalf. Other types of CCs include salary sacrifice contributions and tax-deductible personal contributions.

The maximum amount that can be split to your spouse is the lesser of:

■ 85% of CCs made in the previous financial year (ie, 2023/24), and

■ The CC cap for that financial year (ie, $27,500 in 2023/24).

EXAMPLE

Alex and Kat are parents to three young children. Kat has taken time off work to care for their children and has much less superannuation than Alex.

After speaking to their financial adviser, they decide to split the $20,000 in SG contributions that Alex received from his employer last financial year (2023/24). In August 2024, Alex applies to his superannuation fund to transfer as much of his CCs as he can to Kat.

Alex is able to split 85% of his CCs which provides a much-needed boost of $17,000 to Kat’s retirement savings.

Rules for the receiving spouse

An individual can apply to split their CCs at any age, but the receiving spouse must be either:

■ Under preservation age (currently age 60 if born on 1 July 1964 or later), or

■ Aged between their preservation age and 65 years, and not retired at the time of the split request.

In other words, if the receiving spouse has reached their preservation age and is retired, or they are 65 years and over, the application to split your CCs will be invalid.

Benefits of contribution splitting

Contribution splitting is an effective way of building superannuation for your spouse and can manage your total superannuation balance (TSB) which can have several advantages, including:

■ Equalising your superannuation balances to make best use of both of your “transfer balance caps” (TBC) which can maximise the amount you both have invested in tax-free retirement phase pensions. Note, the TBC limits the amount that a person can transfer to retirement phase pensions in their lifetime – this limit is currently $1.9 million in 2024/25.

■ Optimising both of your TSBs to:

■ Access a higher non-concessional (after-tax) contribution cap (as the amount you can contribute to superannuation depends on your TSB)

■ Access the carry-forward CC rules and make larger CCs (note, the option to utilise these rules is restricted to those with a TSB below $500,000 on the prior 30 June)

■ Qualify for a government co-contribution

■ Qualify for a tax offset for spouse contributions

■ Boosting your Centrelink entitlements by transferring funds into a younger spouse’s accumulation account if your spouse is under Age Pension age.

Last word

As always, there are eligibility requirements that must be met and deciding what is best for you will depend on your personal circumstances. For this reason, you may want to seek personal financial advice to determine whether contribution splitting is right for you and your spouse.

Breaking up (by text) is hard to do

A recent decision by the Full Federal Court around a man’s tragic death by suicide clarified the standing of a defacto spouse in the context of a non-lapsing death benefit nomination on a life insurance policy made by the deceased person.

Just prior to C’s death in September 2019 the death benefit under his insurance policy was valued at $1.1 million, with the death benefit nomination in favour of his de facto spouse, N, having been made in December 2018.

On the night of his death, C sent a text message to his sister, purporting to be his last will and testament and indicating his wish that all his assets should pass to his family, with N receiving nothing. The text was not copied to N and it was later established that it was sent while C was under the influence of cocaine and alcohol.

The trustee of the policy took the view that the defacto relationship had continued right up to the time of C’s death and that N was therefore entitled to the death benefit. This decision was challenged by C’s family before the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA), arguing the text was evidence that the relationship between C and N had ended before C’s death.

However, AFCA decided that relationships have their ups and downs and people say and write a lot of things they don’t mean all the time. This meant the trustee was right, the relationship remained ongoing just prior to C’s death and N was entitled to receive the death benefit.

The family then appealed to the Federal Court, where a single judge ruled that AFCA had erred in law in not construing the text message as proof that C’s relationship with N had come to an end, meaning that N was not a valid beneficiary after all.

Finally (one would think), N appealed to the Full Federal Court, which held unanimously that in the absence of communication from C to N, there needed to be some other course of conduct, such as a refusal to cohabitate, which would clearly be inconsistent with a continuation of the relationship.

Since there was no evidence about such conduct, the Full Court ruled in favour of N. The decision by AFCA was therefore upheld.

This case, with its own peculiar facts, highlights the importance of keeping things like binding death benefits nominations up to date and being clear about spousal relationships, especially when couples live apart.

Small business energy incentive

A little-known tax incentive that is aimed at encouraging businesses to improve energy efficiency is the small business energy incentive (SBEI).

You will have to jump through a few hoops to qualify, but depending on what sort of depreciating assets you have acquired between 1 July 2023 and 30 June 2024 (the bonus period), you may be entitled to a bonus deduction of 20% of the cost of acquiring up to $100,000 of eligible equipment. This is over and above what you would ordinarily claim, so it’s bit like the old investment allowance, but with a $20,000 cap. That’s up to $9,400 extra in your pocket, which may make it worth a look.

The SBEI is available to businesses with an annual turnover of less than $50 million, where they have invested in certain eligible depreciating assets during the bonus period and where one or more of the following apply:

■ there is a new reasonably comparable asset that uses fossil fuel available in the market;

■ the new asset is more energy efficient than the one it is replacing;

■ if not a replacement asset, it is more energy efficient than a new reasonably comparable asset available in the market.

An asset can also be eligible if it is an energy storage, time-shifting or monitoring asset, or an asset that improves the energy efficiency of another asset.

The bonus deduction is available on second hand assets, although the comparable asset must be available in the market as new.

It only applies to businesses, so replacing gas appliances with electric ones in a rental property would not qualify. The bonus deduction does not apply to solar panels or motor vehicles.

If you think you may have a claim, please feel free to contact us.

Click here to view our Glance Consultants August newsletter via PDF